Why SHANTI Matters: Reimagining Nuclear Energy for India’s Clean and Secure Future

S. Ahmad

Nuclear energy is the use of controlled atomic reactions to produce power. At its core, it relies on splitting atoms in a process called fission, which releases large amounts of heat. This heat is then used to generate electricity without producing greenhouse gases. Globally, nuclear energy is valued as a clean, dependable source that complements renewable options like solar and wind.

Whenever nuclear energy enters public discussion, it almost inevitably triggers a mixture of fascination, fear, and confusion. For many citizens, nuclear power exists either as an abstract scientific idea or as a distant, heavily guarded facility associated with rare but dramatic global accidents. This perception has been shaped less by everyday reality and more by selective imagery and incomplete understanding.

In truth, nuclear energy is neither mysterious nor inherently dangerous; it is a carefully regulated scientific process that has reliably powered homes, hospitals, research institutions, and industries across the world for decades. At its core lies nuclear fission—the controlled splitting of atoms to generate heat, which is then converted into electricity without releasing carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases.

In a century increasingly defined by climate change, energy insecurity, and geopolitical uncertainty, this defining characteristic alone makes nuclear power impossible to dismiss. As nations struggle to decarbonise their economies while ensuring uninterrupted electricity supply, nuclear energy stands out as one of the few sources capable of delivering large-scale, round-the-clock, low-carbon power. It is within this urgent global and national context that the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025 must be understood.

The SHANTI Bill is not a routine piece of legislation nor a minor policy adjustment. It represents a generational recalibration of India’s nuclear governance framework, reflecting both technological maturity and strategic self-confidence. By consolidating and modernising India’s nuclear laws into a single, coherent, future-ready framework, the Bill seeks to align nuclear energy with India’s clean energy transition, industrial growth, and long-term strategic autonomy.

India’s nuclear journey has always been distinctive, shaped by caution, sovereignty, and long-term thinking. The Atomic Energy Act of 1962 laid the legal foundation for the peaceful use of atomic energy, replacing the immediate post-independence legislation of 1948. That law reflected the realities of a world where nuclear technology was scarce, strategically sensitive, and inseparable from national security concerns. The State retained exclusive control, not out of suspicion of innovation, but out of recognition that nuclear energy demanded exceptional responsibility.

Subsequent legislative changes carefully expanded the ecosystem without diluting sovereign oversight. Amendments in 1986, 1987, and 2015 allowed government-owned companies and joint ventures to participate in nuclear power generation, reflecting India’s growing institutional capacity and technical confidence.

The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act of 2010 further strengthened public trust by introducing a no-fault liability regime, ensuring that victims would be compensated swiftly in the highly unlikely event of a nuclear accident. Together, these laws created a robust yet conservative framework that prioritised safety, accountability, and national interest.

However, laws are products of their time. India’s energy landscape today is fundamentally different from that of even a decade ago. Electricity demand is rising rapidly, driven by urbanisation, expanding digital infrastructure, data centres, electric mobility, and advanced manufacturing. Simultaneously, India has made clear and ambitious climate commitments, including achieving net-zero emissions by 2070. While renewable energy sources such as solar and wind have expanded impressively, they remain inherently intermittent. Sunlight fades and winds calm, but modern economies require stable, uninterrupted power.

It is here that nuclear energy acquires renewed relevance. Nuclear plants operate at high capacity factors, providing steady base-load power regardless of weather or time of day. As energy experts often note, no large industrial economy has successfully decarbonised without a strong foundation of firm, clean power. Nuclear energy fills precisely this gap.

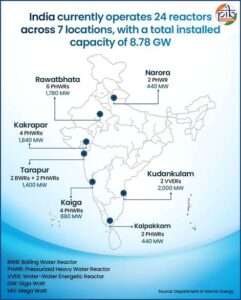

At present, nuclear power accounts for about 3 per cent of India’s electricity generation, with an installed capacity of 8.78 gigawatts. While modest in proportion, this capacity has delivered consistent and reliable output. With ongoing reactor projects and international cooperation on indigenous 700 MW and 1000 MW designs, nuclear capacity is projected to reach 22.38 GW by 2031–32. Yet even this expansion is only a transitional step. India’s long-term Nuclear Energy Mission aims to scale capacity to 100 GW by 2047, aligning nuclear power with the broader vision of Viksit Bharat at the centenary of Independence.

The Union Budget 2025–26 provided tangible momentum to this ambition by allocating ₹20,000 crore for the development and deployment of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). These reactors represent a technological shift in nuclear energy. Smaller in size but advanced in safety features, SMRs offer flexibility in siting, lower upfront capital requirements, and enhanced passive safety systems. They are particularly well suited to India’s diverse geography and emerging energy needs, including industrial clusters, remote regions, and future hydrogen production.

India’s indigenous efforts further underline this strategic intent. Initiatives led by the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, such as the Bharat Small Modular Reactor and high-temperature reactors designed for hydrogen generation, signal that India does not merely seek to import nuclear solutions. Instead, it aims to innovate, adapt, and eventually lead in nuclear technology suited to developing and climate-constrained economies.

Yet ambition without institutional reform risks stagnation. Existing nuclear laws, crafted for an era of limited capacity and exclusive public-sector operation, do not provide the flexibility or scale required for this next phase of expansion. The SHANTI Bill addresses this gap directly. By repealing and consolidating the Atomic Energy Act of 1962 and the Civil Liability Act of 2010, it creates a unified and modern legal framework that balances innovation with safety, participation with oversight, and growth with accountability.

One of the most debated aspects of the Bill is the introduction of limited private sector participation. For the first time, private companies are permitted to operate nuclear power plants, generate electricity, manufacture equipment, and undertake select fuel-cycle activities, all under strict regulatory supervision. This does not represent a withdrawal of State authority. Rather, it acknowledges a practical reality: achieving 100 GW of nuclear capacity requires capital investment, manufacturing depth, and technological capability beyond what the public sector alone can provide.

Crucially, the Bill draws firm red lines. All activities involving radiation exposure require prior safety authorisation, and the most sensitive domains—such as uranium enrichment, spent fuel management, reprocessing, and high-level radioactive waste handling—remain exclusively under Central Government control. Sovereignty and security are thus preserved, even as participation widens.

Public confidence is further strengthened through enhanced regulatory oversight. By granting statutory status to the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, the SHANTI Bill reinforces the independence, authority, and credibility of nuclear regulation in India. In any nuclear programme, a strong and visibly independent regulator is the foundation of public trust. This reform recognises that expansion without rigorous oversight is neither safe nor sustainable.

The Bill also introduces a more nuanced and internationally aligned liability framework. Instead of a uniform liability cap, liability is now graded based on the characteristics and risk profile of individual nuclear installations. This approach improves realism without weakening victim protection. Complementary mechanisms—including Claims Commissioners, a Nuclear Damage Claims Commission for severe incidents, and structured dispute resolution—ensure that accountability is clear, accessible, and enforceable.

Importantly, the SHANTI Bill looks beyond electricity generation. It explicitly recognises the expanding role of nuclear and radiation technologies in healthcare, agriculture, industry, and research. From cancer treatment and food preservation to industrial imaging and scientific innovation, nuclear science already touches daily life in ways that remain largely invisible. By creating a clearer regulatory environment and limited exemptions for research activities, the Bill encourages innovation while maintaining safety safeguards.

At its core, the SHANTI Bill is an expression of strategic confidence. It reflects a nation secure enough in its institutions to open its nuclear sector cautiously, without compromising control. It strengthens emergency preparedness, embeds security and safeguards across the nuclear value chain, and aligns nuclear energy with India’s broader development and climate goals.

As India charts its energy future, the question is no longer whether nuclear power has a role to play. The scale of climate risk, energy demand, and industrial ambition makes that role unavoidable. The real question is whether India can design a nuclear framework that is safe, sovereign, inclusive, and future-ready. The SHANTI Bill answers that question with clarity and conviction.

If implemented with seriousness, transparency, and institutional discipline, this legislation may well be remembered as the moment when India decisively bridged the gap between energy ambition and energy capability—quietly, responsibly, and with a clear-eyed focus on the decades ahead.

The article is based on the inputs and background information provided by the Press Information Bureau (PIB) Author is Writer, Policy Commentator. He can be mailed at kcprmijk@gmail.com

Comments are closed.