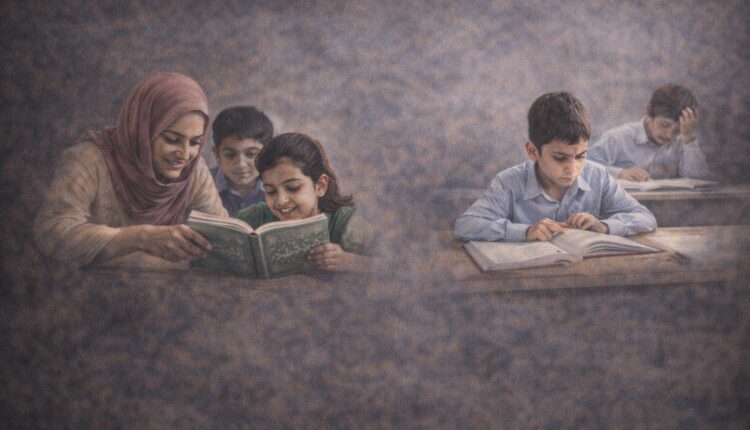

Why Mother Tongue Matters in the Classroom?

Firdous Ahmad Najar

“When education is delivered in the mother tongue, comprehension and memory develop together. When it is not, learning becomes a two-stage struggle—decoding unfamiliar words first, and understanding much later, if at all.”

Comments are closed.