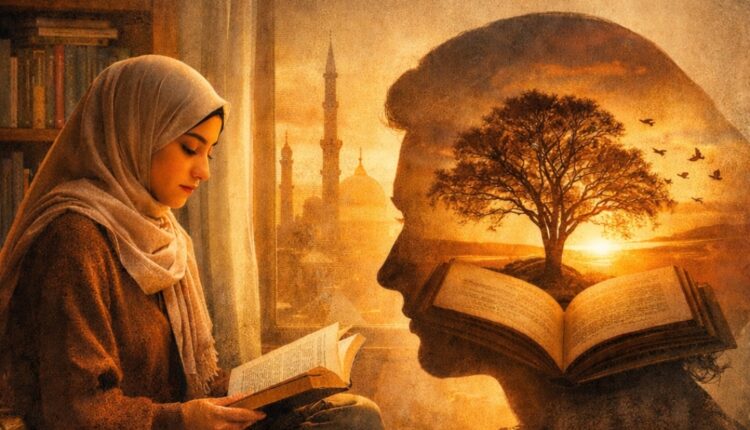

What We Read Quietly Shapes Who We Become

Mir Qurrat-ul-Ain

“A book does not end at the last page—it stays. Over time, it influences how we respond to situations, how we understand relationships, and the standards we quietly internalize. That is why I hesitate before choosing a book, even after years of reading. Reading shapes us slowly, often invisibly, until we realize it has altered how we see the world.”

We tend to think of reading as harmless, just stories, just words, just a way to pass the time. But words are never passive. They slip quietly from the page into the mind, and from the mind into the soul, shaping our thoughts long before we are aware of the change. In recent years, reading has experienced a resurgence in popularity. In an age of endless scrolling and shrinking attention spans, reading has also become something we display rather than something we sit with. Social media feeds are filled with aesthetic bookshelves, underlined passages, and trending recommendations.

On the surface, this feels reassuring. Yet as I scroll, I find myself uneasy not because people are reading, but because reading has become visible without becoming meaningful. The act is celebrated; the impact is rarely questioned. I often hear parents say with pride, “My children don’t waste money; they only buy books.” I smile when I hear this, but the smile pauses halfway. Buying books is admirable, no doubt. Yet books are not equal in influence.

The real question is not how many books enter a home, but what kind of ideas are being invited into young minds. This concern comes from lived experience. It has been more than ten years since I began reading English and Urdu literature, and even today, I hesitate before choosing a book. I ask, I search, I reflect, and only then do I read. I do so because I am deeply aware of one truth: a book does not end at the last page. It stays. Over time, it influences how we respond to situations, how we understand relationships, and the standards we begin to internalize.

Islam places great emphasis on intention, or niyyah, in every action, reminding us that even ordinary habits carry moral weight. Reading, too, is an act of both the mind and the heart. The first revelation itself was a command to read, but to read with awareness, purpose, and reflection. In Islamic thought, knowledge is not valued merely for accumulation or display; it is meant to shape character, cultivate discernment, and guide a person toward wisdom. When reading is approached with this consciousness, it becomes more than a pastime; it becomes a means of inner refinement. Islamic teachings repeatedly remind us that knowledge is a trust (amanah). What we take into the mind is meant to settle in the heart and be reflected in our conduct. Reading, then, is not a neutral act; it is one that quietly shapes intention, character, and moral sensitivity.

This awareness was reinforced during a recent, unsettling moment. While browsing a teenager’s bookshelf, I noticed books with extreme and disturbing themes, promoted through bold, provocative language. I did not know what the book was about, and I was careful not to judge it solely by its cover. Still, the title gave me pause.

I asked gently, “What kind of books are you reading?”

She replied casually, “I’ve just bought it. I haven’t read it yet.”

I advised her not to buy or read such books, not out of condemnation, and not because I believed the book was necessarily without value. My concern was simpler and more responsible. Titles matter. They are often the first doorway through which ideas enter the mind. At an age when emotional maturity is still developing, repeated exposure to such themes, without guidance or context, can quietly influence perceptions of relationships, family, and respect. Islam places particular responsibility on protecting young hearts and minds during their formative years.

Guidance is not about control, but about caring about ensuring that what enters the mind does not harden the heart or dull one’s sense of compassion and responsibility. What makes this more concerning is that we live in a time of abundance, not scarcity. There is no shortage of books that inspire, heal, and guide, strengthening character, deepening reflection, and drawing one closer to faith and wisdom. Yet, social media has amplified confusion. Books trend not because they offer depth, but because they provoke reactions or look visually appealing. Reading has become something to display, rather than something to absorb. In such spaces, wisdom is often overshadowed by virality.

This question becomes especially clear to me in everyday conversations. My non-reader friends often ask, “What do you even get from reading?” or “What kind of books do you read?” To them, novels usually mean love stories and little else. I do not blame them; when reading has never been part of one’s inner life, it is difficult to imagine its reach. I often smile at these questions, knowing how limited that picture is. How do I explain that literature carries history, faith, philosophy, pain, hope, and transformation within it? Does it shape not only what we think, but also how we feel and what we say? Sometimes, I wish they could sit beside me in silence and witness what reading has done to me, not only through English literature, which has expanded my thinking, but also through Urdu literature, which has shaped my language, emotions, and spiritual sensitivity. Some experiences are not argued or explained; they are slowly absorbed into our understanding.

Reading is a powerful habit, but only when practiced with awareness. When reading becomes merely a trend, an aesthetic, or a form of social approval, its deeper purpose quietly fades. In Islam, we are reminded that the heart is shaped by what it repeatedly consumes. Just as careless eating affects the body over time, careless reading leaves its mark on the mind, often in ways we recognize only much later. This is not a call to avoid difficult or uncomfortable themes. Literature has always reflected human struggle, doubt, and vulnerability. Instead, it is an invitation to pause and ask a simple but essential question: What is this book giving me in return for my time and attention? Is it deepening understanding, or merely occupying space? Parents, educators, and readers all share this responsibility. Encouraging children and young adults to read is essential, but guiding them toward thoughtful, value-conscious reading matters just as much. Conversations about books, why they matter, what they leave behind, and how they shape perspective are often more influential than the books themselves.

Ultimately, reading is not just a pastime; it is a quiet, lifelong companion. Trends will fade, shelves will change, and popular titles will be replaced, but the ideas we carry within us remain. They shape how we think, how we speak, and how we understand the world around us. Every book we read is a seed. Some take root and grow into clarity and wisdom; others pass through us without nourishment. In Islamic thought, the heart (qalb) is not merely an emotional center; it is the core of understanding and moral awareness. What we repeatedly expose ourselves to slowly becomes part of who we are.

As Imam Al-Ghazali wisely reminded us, “Knowledge without action is wasteful, and action without knowledge is foolish.”

Perhaps, then, the question is not simply how much we read, but how mindfully we choose what we allow to shape us.

Reading more is good. Reading with purpose is transformative.

Author Mir Qurrat-ul-Ain is a Ph.D. Scholar in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at NIT Srinagar. She can be reached at mirqurrat@gmail.com

Comments are closed.