The Forgotten Economist: Revisiting Baqir al-Sadr’s Vision

Abid Ali Mir

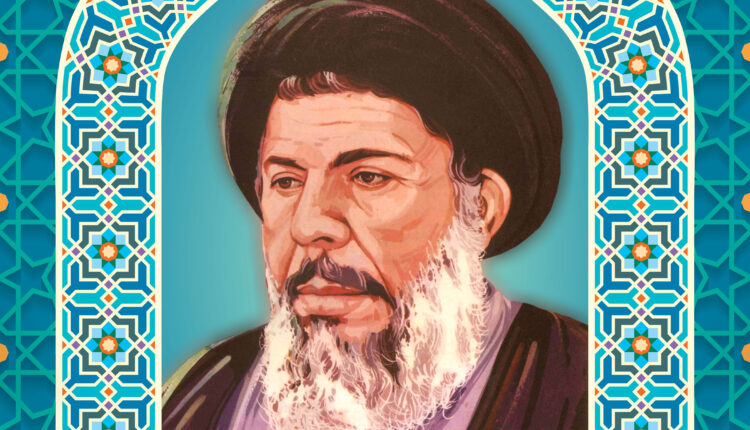

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr stands as one of the most luminous and intellectually powerful figures of the 20th century Islamic world. He became a mujtahid (a qualified independent jurist) at the remarkably young age of 25. As a leading Shi’a scholar, jurist, and philosopher, he not only shaped the religious and philosophical discourse of his time but carved out an entirely new direction in Islamic economics. His ground-breaking book, Iqtisaduna (“Our Economics”), remains a monumental work and an intellectual legacy that continues to guide scholars, economists, and institutions across the globe. More than just a response to prevailing ideologies, Iqtisaduna was a bold, visionary effort to articulate a comprehensive Islamic economic system that is morally grounded, spiritually enriched, and intellectually superior to both capitalism and socialism.

Written during an era dominated by the ideological conflict between Western capitalism and Soviet socialism, al-Sadr’s work courageously presented Islam as not merely a religion confined to rituals, but as a total and self-sufficient system encompassing economic, political, and ethical dimensions. He did not resort to polemics or emotional rhetoric; instead, he embarked on a meticulous intellectual critique of both systems, exposing their foundational flaws and highlighting their inability to deliver justice, equity, or spiritual meaning.

In Iqtisaduna, al-Sadr organized his thought in three core parts: a critique of capitalism, a critique of socialism (particularly Marxism), and a rigorous formulation of an Islamic economic model. His critique of capitalism was profound, identifying its fundamental ethos rooted in materialism, individualism, and secularism as the source of human alienation and moral decay. Capitalism, in his view, reduces economic activity to a pursuit of personal gain, disregarding divine guidance, ethical responsibility, and the wellbeing of the broader society. While acknowledging capitalism’s efficiency and technological advancement, al-Sadr was unrelenting in his critique of its consequences: exploitation, economic inequality, and spiritual emptiness.

His evaluation of socialism was more balanced, recognizing its genuine concern for justice and the working class. However, al-Sadr dismantled the core assumptions of Marxist theory, especially its denial of metaphysical truth and its obsession with materialistic determinism. He argued that reducing human history to class struggle and economics strips life of its spiritual essence. Islam, by contrast, upholds justice without annihilating individual ownership or erasing the role of divine purpose in human affairs. He rejected socialism’s complete abolition of private property and excessive centralization of the economy, noting that such approaches kill personal initiative and smother economic creativity.

What sets Iqtisaduna apart from all other economic writings of its time is not merely its critique of competing ideologies, but its positive vision a robust, divine-centered economic system that draws from the Qur’an, the teachings of the Prophet (PBUH), and the insights of Islamic jurisprudence. Al-Sadr redefined Islamic economics not as a patchwork of legal rulings, but as a holistic worldview rooted in divine sovereignty (Hakimiyyah) and guided by human stewardship (Khilafah). In this vision, economics is not separate from ethics or spirituality; rather, it is an arena where values like justice, equity, generosity, and responsibility must reign supreme.

One of his most original contributions was his theory of ownership. He proposed a tripartite classification: private ownership, public ownership, and state ownership. Unlike capitalism, which sanctifies private property to the detriment of the community, and socialism, which eliminates it altogether, al-Sadr presented a model in which ownership is a trust from God. Each type of ownership serves a specific social function and must adhere to Islamic ethics. This balanced framework ensures that individual rights are protected, while collective welfare and justice are not compromised.

Al-Sadr also addressed the market system with deep insight. He accepted the idea of markets but insisted they must operate within a framework of Islamic law and moral integrity. Markets must be free from riba (interest), fraud, monopoly, and speculative practices (gharar). In this system, the state is not a tyrant but a guardian responsible for regulating the market, ensuring just prices, and intervening when necessary to uphold the public good. Instruments like zakat and khums serve as powerful redistributive tools that help curb inequality and sustain social solidarity.

Perhaps one of the most revolutionary aspects of Iqtisaduna is al-Sadr’s critique of riba (interest). He did not merely quote Qur’anic prohibitions; he offered a philosophical and economic critique of interest-based transactions. He demonstrated how riba institutionalizes inequality, burdens the poor, and turns money into a tool of oppression. Instead, al-Sadr championed risk-sharing, investment partnerships (mudarabah), and joint ventures (musharakah) models that emphasize fairness, accountability, and mutual benefit. This vision has since become the backbone of modern Islamic banking and finance.

In his view of labor and production, al-Sadr uplifted the status of the worker. He neither commodified labor as capitalism does nor absorbed it into the state machinery like socialism. Labor, for him, is an honorable human contribution, with both spiritual and material worth. He proposed ethical profit-sharing arrangements between capital and labor that reflect cooperation, not exploitation.

Remarkably, Iqtisaduna did not go unnoticed in Western academic circles. Despite being deeply rooted in Islamic tradition, al-Sadr’s intellectual clarity, systematic reasoning, and ethical depth attracted the attention of non-Muslim scholars. Charles Tripp, a renowned British political scientist, in his book Islam and the Moral Economy (Cambridge University Press), highlighted al-Sadr’s critique of capitalism and praised Iqtisaduna as a powerful synthesis of moral vision and economic insight. Tripp recognized that al-Sadr had presented a genuine alternative to both dominant Western ideologies, one that could engage the global discourse with seriousness and depth.

Similarly, Chibli Mallat, a prominent Lebanese legal scholar writing within Western academic traditions, described Iqtisaduna as one of the greatest achievements in Islamic economic and legal thought. In his book The Renewal of Islamic Law: Muhammad Baqir as-Sadr, Najaf and the Shi’i International (also published by Cambridge University Press), Mallat referred to Iqtisaduna as the most vivid example of updating classical jurisprudence to address modern challenges what he termed “aggiornamento” of Islamic law.

Al-Sadr’s vision became even more relevant during the global financial crises of the 21st century, particularly the collapse of interest-based banking systems in 2008. As the world searched for ethical alternatives, his work provided not just a critique, but a constructive blueprint. Islamic banks across the Muslim world especially in the Middle East and Southeast Asia adopted many of his principles, whether directly or indirectly. His ideas reshaped not only Shi’a scholarship but also influenced Sunni thinkers, policymakers, and practitioners of Islamic finance worldwide.

Iqtisaduna is not merely a book; it is an intellectual revolution. It dares to imagine a world where economics serves humanity, where wealth is not worshipped but managed as a trust from almighty Allah, and where justice is not a slogan but a system. Martyr Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr’s contribution to Islamic thought is unparalleled in its depth, precision, and foresight. He stood as a beacon of knowledge, a soul of courage, and a voice of reform in an age dominated by ideological confusion. His legacy will continue to inspire a global quest for a more ethical, just, and spiritually anchored economic order. He was not only a scholar of his time but a timeless architect of economic justice. What I’ve written may not do full justice to his legacy, but it’s my humble tribute to a thinker whose words I’ve carried with me since my teenage years. His ideas shaped the way I view the world, and as someone who has been deeply influenced by him, I felt it was important to write something in his honor.

Abid Ali Mir is a Kashmiri writer, occasional poet and, thinker advocating Islamic finance, social justice, environmental preservation, and action against plastic pollution. He can be reached at abidmir0078@gmail.com

Comments are closed.