Sadaqah-e-Jariyah: The Architecture of Good Deeds That Lives On

“Build deeds so durable that even absence cannot end their impact.”

Dr. Aadil Zeffer

“Libraries, learning spaces, and shared knowledge are not cultural luxuries; they are social infrastructure, as vital to dignity and resilience as roads or clinics.”

The most meaningful charity is not consumed in a moment but sustained across lives. Across civilisations and historical epochs, societies have distinguished between charity that alleviates immediate distress and giving that reshapes the conditions of life over time. The latter which is often quieter, less visible, and slower to yield results, has consistently proven more transformative.

In Islamic ethical thought, this principle is crystallised in the idea of “Sadaqah-e-jariyah,” a form of giving whose benefits continue to flow long after the initial act, creating a moral architecture that links the present to the future. The emphasis on continuity is neither sentimental nor abstract; it reflects a deeply practical understanding of how social goods are produced, sustained, and transmitted across generations.

The moral logic behind lasting charity is articulated with striking clarity in Prophetic teaching, which holds that when a person dies, three forms of good continue to accrue: ongoing charity, beneficial knowledge, and righteous offspring who carry forward ethical responsibility. The Qur’anic insistence on thoughtful, purposeful giving reinforces this ethic by associating generosity with foresight, sustainability, and social multiplication rather than mere display. Charity, in this framework, is not measured only by intensity or visibility but by durability and by its capacity to endure, adapt, and remain useful over time.

Historically, this ethic found institutional expression in the system of waqf, or charitable endowment. Across the Islamic world, from North Africa to Central Asia, endowments financed schools, hospitals, libraries, water systems, caravanserais, and public kitchens. These were not sporadic acts of benevolence but carefully designed structures governed by rules of accountability and continuity.

Many of the world’s oldest educational and medical institutions emerged from such endowments, demonstrating how ethical intention, when combined with institutional design, can produce public goods that outlast dynasties and political regimes. What distinguished these endowments was not scale alone but orientation: they invested in people, knowledge, and collective capacity rather than short-lived relief.

This logic of enduring philanthropy is not confined to any single religious or cultural tradition. In East Asia, community-funded schools and academies historically tied learning to collective responsibility, embedding education within social obligation. In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, extended-family and village-based scholarship pools have sustained generations of teachers, nurses, and administrators who later reinvest their skills in local development.

Western universities themselves, from medieval colleges to contemporary scholarship endowments, stand as monuments to a culture of giving that privileges human potential over immediate consumption. Across these diverse contexts, a shared conviction emerges: the most resilient forms of charity are those that strengthen institutions, preserve knowledge, and multiply capability.

Seen in this broader comparative light, sadaqah-e-jariyah appears not just as a religious injunction but as a universal social principle as well- an ethics of investment in human and institutional futures. It encourages communities to move from reactive generosity to intentional design, from episodic aid to structured care. The question it poses is simple but demanding: not merely how much we give, but what kind of world our giving helps to build.

Educational initiatives offer one of the clearest illustrations of this principle. A single scholarship may appear modest in financial terms, yet its cumulative effects can be profound. A child supported through schooling may later become a teacher, doctor, engineer, public servant, or community organiser, each role generating further social benefit. When scholarship programmes incorporate mentorship, peer tutoring, and alumni engagement, they create self-reinforcing cycles of support that reduce dependence on external funding. Over time, such initiatives cultivate cultures of learning, aspiration, and civic responsibility that extend well beyond individual beneficiaries.

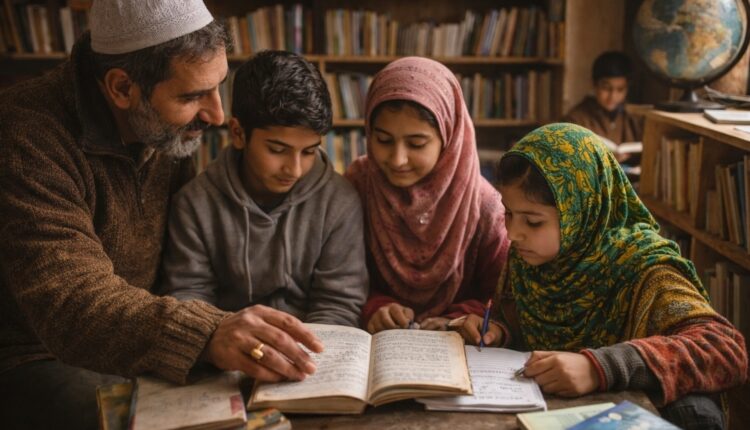

Similarly, modest public libraries and shared learning spaces exemplify how small, durable investments can yield expansive returns. A shelf of books in a community centre, mosque, or school preserves collective memory, stimulates curiosity, and offers an alternative to the distractions of purely consumptive culture. When learning spaces remain open, inclusive, and responsive to local needs-hosting reading circles, literacy classes, or informal discussions- they become social infrastructure as vital as roads or clinics. Their value lies not only in access to information but in the habits of reflection, dialogue, and mutual respect they foster.

From a civic perspective, the case for sadaqah-e-jariyah is as compelling as its theological grounding. In contexts where public services are uneven or overstretched, well-designed private philanthropy can complement state provision without undermining it. More importantly, durable giving socialises the idea that knowledge, health, and dignity are shared goods rather than private luxuries. It builds social capital- trust, reciprocity, and collective responsibility- resources that are essential for democratic life and social resilience yet difficult to generate through market mechanisms alone.

For individuals and communities seeking practical pathways to such lasting impact, several principles merit attention. Clarity of purpose is essential: donors should define beneficiaries and goals with precision rather than relying on vague intentions. Modest, well-managed initiatives often outperform grand but unsustainable projects. Transparent governance, local participation, and simple reporting mechanisms ensure accountability and trust. Planning for succession, so that projects survive the absence of any single benefactor, is not merely administrative prudence but an ethical obligation. Above all, effective sadaqah-e-jariyah responds to local rhythms and needs, recognising that durability arises from relevance as much as from funding.

At its deepest level, sadaqah-e-jariyah addresses a universal human concern: the desire for one’s actions to matter beyond the limits of an individual’s lifespan. Yet it is not an exercise in legacy-building for its own sake. Properly understood, it is a form of social technology and an approach to resilience that reduces vulnerability, counters exclusion, and sustains civic life. It asks donors to exchange spectacle for structure, immediacy for foresight, and recognition for quiet continuity.

In an age increasingly marked by performative generosity and fleeting attention, the counsel to “build what lasts” acquires renewed urgency. Investing in minds rather than moments, in institutions rather than impressions, and in shared futures rather than personal acclaim is both an ethical and practical imperative. A scholarship quietly renewed each year, a reading room steadily used, a learning space kept open, etc.- these are the architectures of good deeds that endure. They do not announce themselves loudly, but they travel far, carrying mercy, knowledge, and dignity across generations. Jazakallahu Khayran…

Dr. Aadil Zeffer is a former Cultural Ambassador (FLTA) to the USA and a former faculty member at TVTC, Saudi Arabia. He can be reached at aadil.sofi@fulbrightmail.org

Comments are closed.