Kashmir: Where Stone Learned to Speak and Thought Learned to Fly

Mohammad Muzaffar Khan

“Kashmir’s story is not one of isolation but of profound connection. It is a land where civilizations paused, reflected, and left behind their finest thoughts in stone, verse, and vision.”

Hidden behind towering mountains and veiled in snow-fed silence, Kashmir has never truly been remote. The enclosing ranges did not shut the world out; instead, they gathered it in. For centuries, this valley stood as a quiet yet powerful witness to the meeting of civilizations, a crucible where ideas, faiths, and artistic traditions encountered one another and fused into something rare and luminous. Here, architecture rose like frozen music, philosophy shimmered with daring thought, and culture flowed outward to shape lands far beyond the confines of the Valley.

Cradled by the Himalayas, Kashmir lay at the heart of Central Asia’s great cultural exchanges. Persian elegance, Gandharan realism, Gupta refinement, and later Islamic aesthetics all found refuge in this natural sanctuary. From the Mauryan emperor Aśoka to the Kushana rulers Kanishka and Huviska, from a period of Gupta suzerainty to the independent glory of King Harsa, Kashmir absorbed influences without surrendering its soul. Instead, it transformed them. By the eighth and ninth centuries, the Valley had entered its classical age, politically confident, culturally radiant, and artistically fearless.

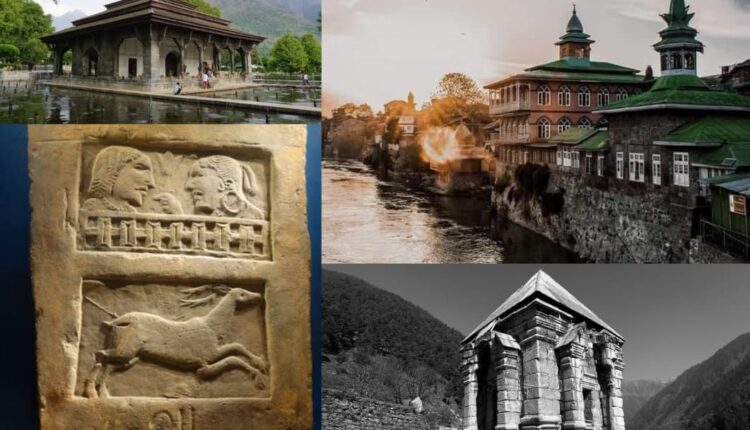

Of all the arts mastered by the people of Kashmir, architecture reigned supreme. Beginning around the second century A.D., Kashmiri builders developed a tradition that would soon astonish the ancient world. Massive blocks of stone were quarried and carved with scientific precision, assembled with assured confidence, and raised into monuments of enduring power.

Without any visible period of experimentation, this architectural style appeared fully mature, monumental, and refined, as though stone itself had learned discipline and grace in the hands of Kashmiri craftsmen.

The most dazzling expression of this genius is the Martand Sun Temple, built by the great Lalitaditya in the eighth century. Even in ruin, it commands awe. Its vast courtyard, bold trefoil arches, and towering walls once stood against the eternal snows like a hymn carved in stone.

When it stood in its prime, few sights could have rivalled its splendour, symmetrically elevated against a mountain backdrop and opening onto the lonely majesty of the sky. At Parihaspura, Lalitaditya’s ambition reached even further, leaving behind ruins that testify to an era when Kashmir dared to build on a near-imperial scale.

Earlier centuries had witnessed Kashmir as a flourishing centre of Buddhism. Stupas rose at Ushkura, the ancient Huviskapura, and at Baramulla, where terracotta and stucco fragments reveal the influence of the Indianised Gandhara style.

At Harwan, an extraordinary tiled courtyard came to light, its terracotta plaques stamped with motifs drawn from more than half a dozen ancient civilizations. Nowhere else in India does such a synthesis exist, where foreign and local elements meet so naturally and speak in a shared visual language. Yet time reshaped belief. By the reign of Avantivarman in the latter half of the ninth century, Buddhism had yielded ground to Hinduism.

Art took on a more medieval character, but it never lost its classical dignity. The temples of Avantipur and the exquisite black basalt sculptures of Vishnu and Shiva reveal a quieter refinement, proving that grandeur can give way to depth without loss of beauty.

If Kashmir taught stone to speak, it also taught thought to soar. The Valley’s greatest contribution lies in the realm of philosophy, particularly in Kashmir Shaivism, a bold system of Realistic Idealism. Unlike Vedanta, which regarded the universe as illusion, Kashmir Shaivism affirmed the reality of the world as a manifestation of the ultimate truth. Liberation was not an escape from existence but a recognition of its true nature.

This revolutionary vision was shaped by thinkers such as Somananda, Utpala, and Khemaraja, and reached its most luminous expression in Abhinavagupta, whose genius illuminated metaphysics, aesthetics, and theology alike. His influence continues to echo through Indian philosophical thought.

Kashmir’s literary legacy is equally resplendent. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini stands as India’s first true historical chronicle, meticulous in detail yet poetic in spirit, a monumental landmark in the annals of Indian history. After him came Jonaraja, Srivara, Pranjna Bhatta, and others who treated history as a sacred responsibility.

Poets like Kshemendra, Somadeva, and Bilhana enriched Sanskrit literature, while Persian poetry flourished under figures such as Mulla Tahir Ghani. The voices of women poets added a rare and moving depth to Kashmiri literature. The philosophical verses of Lalleshwari and the tender lyrics of Arinimal and Habba Khatoon continue to resonate with devotion, longing, and wisdom.

Kashmir also reshaped how poetry itself was understood. Anandavardhana’s theory of Dhvani, refined by Abhinavagupta and later Mammaṭa, transformed literary criticism by revealing poetry as suggestion and resonance rather than mere expression. Meaning, emotion, and beauty were no longer confined to words alone but unfolded in what they evoked.

The arrival of Islam in Kashmir did not bring violent rupture but gradual synthesis. Architectural forms evolved locally rather than being imposed from outside.

The tomb of Zain-ul-Abidin’s mother, influenced by Persian-Turkish styles, stands as a symbol of transition, while Zain-ul-Abidin himself emerged as a visionary ruler who harmonized Hindu and Muslim traditions, anticipating the pluralism later associated with Emperor Akbar.

Wood and brick became dominant materials, adorned with glazed tiles and intricate jali screens. Mosques such as Shah Hamdan, Madni Sahib, and the old Jama Masjid at Pampur exemplify a style found nowhere else in the Islamic world.

Comments are closed.