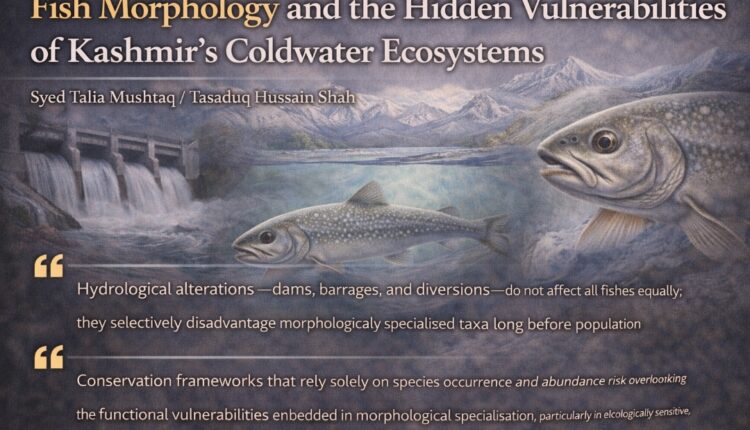

Fish Morphology and the Hidden Vulnerabilities of Kashmir’s Coldwater Ecosystems

The article examines the absence of morphological considerations in Indian freshwater fish conservation policy, with particular reference to high-altitude ecosystems.

Syed Talia Mushtaq / Tasaduq Hussain Shah

“Hydrological alterations—dams, barrages, and diversions—do not affect all fishes equally; they selectively disadvantage morphologically specialised taxa long before population collapse becomes visible.”

Comments are closed.