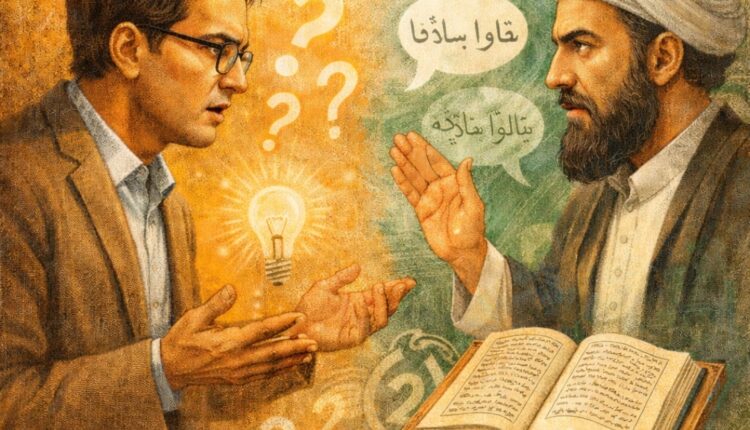

Disagreement in Scholarship: Between Reason and Reverence

Javid Jawad

“Faith does not lose its ground when questions are asked; it loses credibility when answers are replaced with mockery and moral posturing.”

Recently, I found myself engaged in a discussion with a friend on an intellectual issue of shared concern. He holds a doctoral degree and is also a graduate of a reputed Dār al-ʿUlūm—credentials that naturally create the expectation of depth, patience, and ethical conduct in debate.

He openly disagreed with my position, which, in itself, is neither unusual nor unwelcome. Disagreement lies at the heart of any healthy scholarly tradition. Without it, intellectual growth stagnates, and thought becomes dogma.

However, when certain points I raised could not be reasonably countered, the discussion took an unfortunate turn. Argument gave way to sarcasm. Instead of responding with reason, my friend mockingly invoked the Qur’anic phrase “qālū salāma”, stripping it of its context, dignity, and moral intent. That moment compelled me to pause and reflect on a deeper question: Is it enough to merely quote the Qur’an, or is it also necessary to understand its meaning, ethical demands, and the conduct it requires from those who invoke it?

The Qur’an is not a rhetorical weapon to be wielded in moments of intellectual discomfort. It is a book of guidance, moral restraint, and ethical clarity. When its words are reduced to sarcastic barbs, used to assert intellectual superiority or silence dissent, we do not elevate faith—we diminish it. Sacred language, when divorced from sacred conduct, becomes hollow.

This experience stirred memories from my childhood in Bandipora, where a curious and troubling narrative once prevailed. Certain college teachers were routinely labelled as “communists.” In some circles, they were even described as members of a so-called “No God Federation” and portrayed as outright deniers of faith. These claims were repeated so often that they gradually acquired the status of unquestioned truths.

At the time, few dared to interrogate these labels. Suspicion replaced inquiry, and hearsay became social fact.

Years later, during my own education, I had the opportunity to interact closely with two such professors who had long carried this stigma. I spent considerable time with them, both inside and outside the classroom. On several occasions, I asked them directly about the allegations levelled against them. They categorically rejected the notion that they were hostile to God or religion. More importantly, my personal observation offered no evidence whatsoever to support the accusations that had followed them for years.

As my exposure widened—through limited reading, engagement with universities, and the company of thoughtful teachers and elders—I began to understand a crucial reality: questioning is not a rebellion against faith; it is often a natural outcome of education. New knowledge inevitably generates questions. Intellectual growth is, by its very nature, unsettling.

It is quite possible that when such questions began emerging in society, some religious preachers and leaders of the time lacked the intellectual tools or confidence to respond adequately. Faced with discomfort, and perhaps fearing the erosion of authority, it may have seemed easier to brand questioning individuals as “communists,” “atheists,” or enemies of faith. In doing so, intellectual challenges were not addressed—they were silenced.

This pattern was reinforced for me recently when an elderly professor shared an incident from the mid-1980s. He had rented a small room in Bandipora market to run tuition classes. Within days, the shop owner asked him to vacate without offering any explanation. After persistent inquiry, the truth emerged: the owner had been told that the professor was spreading communism under the guise of teaching.

Later, it became clear that the allegation had nothing to do with ideology or belief. It was driven purely by personal jealousy and rivalry from another academic. Yet a baseless accusation, amplified by fear and social suspicion, was enough to deprive a respectable teacher of his livelihood and dignity.

These incidents reveal a bitter truth about our social and intellectual climate. Here, asking questions is often treated as a crime. Disagreement is seen as betrayal. Intellectual inquiry is hastily linked to some dangerous “ism” or outright atheism. When dialogue ends, accusations begin. When arguments weaken, character assassination becomes the easiest refuge.

This tendency reflects not the strength of faith, but its insecurity.

What we urgently need is a return to intellectual and moral honesty. The Qur’an must be treated not merely as a source of quotations, but as a moral scale against which our conduct is measured. Disagreement should be recognised as a path to understanding and growth, not as an act of hostility. Questioning minds should be engaged with reason, patience, and ethical seriousness—not silenced through fear, ridicule, or social ostracism.

In this context, it is worth reflecting on figures like Javed Akhtar, a declared atheist. In my view, people like him often do not have as much of a problem with God as they do with those who claim to represent religion. More often than not, it is the conduct adopted in the name of religion—arrogance, intolerance, and intellectual dishonesty—that pushes reflective minds toward doubt, and sometimes even denial.

Perhaps, then, the real divide is not between belief and disbelief. It lies between sincerity and pretence, dialogue and dogmatism, moral confidence and intellectual fear. Faith does not lose its ground when questions are asked; it loses credibility when answers are replaced with mockery and moral posturing.

If we truly believe in the ethical depth of our tradition, we must allow it to be questioned, examined, and understood—not merely quoted.

Author is a Best Teacher Awardee from Bandipora

Comments are closed.