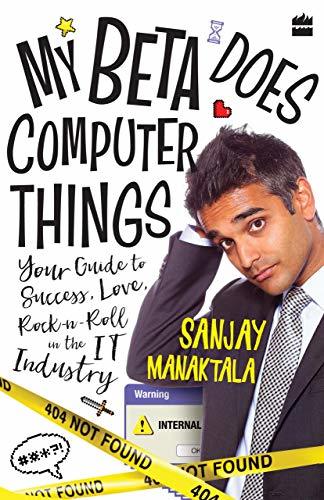

Book Review: My Beta Does Computer Things.

"Sanjay Manaktala’s book challenges the culture of measuring success by titles and salaries, a theme familiar in Kashmiri households.

Peerzada Mohsin Shafi

There are books that inform, books that entertain and then there are those that hold up a mirror to society in ways that are both uncomfortable and liberating. Sanjay Manaktala’s My Beta Does Computer Things, published by HarperCollins India in August 2025, belongs firmly in the third category. At first glance, it seems like a humorous take on India’s fascination with software jobs, but beneath the wit lies a deep social critique. For Kashmir, where conversations around careers are often confined to engineering and government service, the book’s message resonates with unusual force.

Manaktala writes from experience. Having worked as an IT consultant before moving into stand-up comedy, he brings a rare blend of insider knowledge and outsider critique. His prose is conversational, often resembling a late-night chat with a witty friend who is unafraid to point out life’s absurdities. He tells stories of young engineers chasing on-site assignments, parents boasting about “secure” jobs their children dislike and tech workers spending weekends debugging code while secretly dreaming of something else.

Yet the strength of the book is not just in its anecdotes. It lies in the way those anecdotes are framed as symptoms of a larger cultural condition. India’s IT sector, once the symbol of globalization and upward mobility has also become a trap where ambition is measured by titles and pay checks rather than passion or balance. Manaktala argues that the “hustle culture” in tech where overwork is glorified and burnout normalized has erased the boundaries between life and livelihood.

For Kashmiri readers, this critique feels eerily familiar. Here too, families nudge their children towards engineering or medicine or more recently computer science, as if no other professions exist. Added to this is the all-consuming craze for government jobs, which despite shrinking opportunities, continues to dominate the imagination of our youth. In countless Kashmiri homes, conversations about careers remain transactional. “Does the job have security? Does it pay well? Will society respect it?” The questions that should matter “Does it suit my child’s interests? Will it allow them to grow as a person? Will it give them dignity without draining their spirit?” rarely find space.

My Beta Does Computer Things provides a counterpoint to this mindset. By presenting the stories of young Indians trapped in cycles of overwork and disillusionment, it implicitly warns families against repeating the same mistakes. The book insists that careers should not be chosen as insurance policies against uncertainty but as pathways to fulfilment. It reminds readers that success in the modern world is not about joining a rat race but about finding one’s lane, however unconventional it may appear.

One of the book’s most powerful sections discusses how parents use job titles as extensions of their own identities. Manaktala describes social gatherings where fathers brag about their sons working in “big IT companies” while the sons themselves feel invisible within giant corporate systems. The humour here is biting but the underlying sadness is undeniable. For Kashmiris, who often live under immense social scrutiny, these dynamic hits close to home. Too many young people feel burdened by the weight of parental and societal prestige, even when it suffocates their individuality.

“Sanjay Manaktala’s My Beta Does Computer Things is more than a humorous take on India’s IT obsession—it is a mirror held up to our culture of measuring success by titles and paychecks, often at the cost of passion and balance.”

Stylistically, the book is light on jargon and heavy on humour. Manaktala uses jokes, sarcasm and everyday observations to make serious points digestible. You laugh when he describes the absurdity of Indians working night shifts to accommodate American time zones, but the laughter is followed by reflection. Why have we normalized a culture where health and family are sacrificed for a salary slip? For Kashmiri readers, this humor-driven critique can serve as a gentle but persuasive push to rethink career choices.

Another important dimension of the book is its emphasis on work-life balance. Manaktala argues that ambition without boundaries leads to emptiness. He calls out the romanticization of burnout and urges readers to reclaim time for hobbies, relationships and self-care. This message is particularly crucial for Kashmiri youth, many of whom equate struggle with virtue. The notion that “the harder you grind, the more successful you become” often leaves them vulnerable to exploitation, whether in the private sector or while preparing endlessly for government exams.

The book also opens space for an intergenerational dialogue. Parents, especially those in regions like Kashmir where economic opportunities are perceived as limited want stability for their children. But stability cannot come at the cost of individuality. Manaktala’s narrative offers parents a chance to re-evaluate their assumptions, to understand that happiness and dignity can emerge from diverse professions, whether in the arts, entrepreneurship, technology or social service.

“For Kashmiri families where careers are often reduced to engineering, medicine, or government jobs, the book’s message strikes with unusual force. It reminds us that stability cannot come at the cost of individuality.”

For thr readers, the relevance of My Beta Does Computer Things extends beyond career advice. It is in many ways, a cultural intervention. It questions the very foundations on which our definitions of respectability and success rest. It suggests that a society where every parent wants an engineer or a government officer is not just unimaginative but also unjust to the potential of its youth. By showcasing the burnout and dissatisfaction of India’s IT workers, the book warns us of what lies ahead if we continue to push our young people into professions that do not align with their talents or passions.

In conclusion, Sanjay Manaktala has written a book that is both entertaining and urgent. My Beta Does Computer Things uses humour to expose uncomfortable truths, encouraging young professionals to reflect on their choices and parents to widen their perspectives. For Kashmir, where career anxieties and parental pressures run deep, this book arrives as both a cautionary tale and a call to imagination. It deserves to be read, discussed and debated in every household.

About the Author:

Peerzada Mohsin Shafi hails from Anantnag and is an infrastructure columnist.

Comments are closed.