Reviving Sufi Culture in Kashmir: Reclaiming a Shared Soul

Mohammad Muslim

“For centuries, Sufi culture shaped how Kashmiris spoke, prayed, wrote, and lived together—teaching that kindness, humility, and mutual respect were not abstract ideals, but everyday responsibilities.”

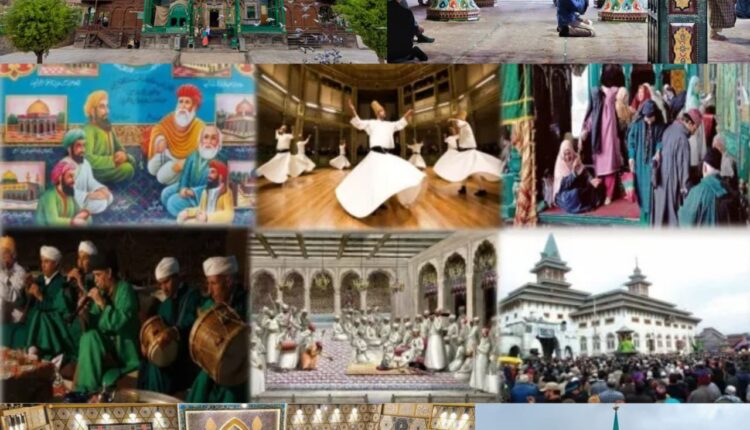

Kashmir’s always had this quiet spiritual heartbeat. For ages, Sufi culture shaped how people spoke, prayed, wrote, and just got along with each other. It wasn’t just about rituals. Sufism taught kindness and patience, and people grew up respecting each other, no matter their background. Shrines felt like the centre of it all—a place to pray, eat together, swap stories, and maybe catch a poetry recital if you were lucky. Lately, though, a lot of folks in the valley feel like that spirit is slipping away. Bringing Sufi culture back matters more than ever. It can rebuild trust, give everyone a sense of pride, and help young people reconnect with something real and meaningful.

Sufism spread into Kashmir through travellers, students, and wandering saints. Their message: spread love and stay humble. They didn’t divide people or erect any kind of roadblocks. Their message: serve others, be truthful to yourself and to others, and stay respectable. And then there’s Sheikh Noor Ud Din Noorani. People know him as Sheikh ul Aalam. His message still convinced many people to be united and equal. People still visit his shrine to seek some comfort and guidance.

These shrines developed into places where ideas developed. Khanqahs and Ziyarats were not only for praying; they were full of stories, poetry, and discussion of what right and wrong were. Figures such as Khawaja Masood Wali and Sheikh Sharif Ud Din Wali created communities because they focused on compassion and equality. When Urs arrived, it became a community celebration like anything else. Communities would prepare, invite people, and celebrate the teachings of these saints. This brought people closer; they felt they belonged.

One could feel the presence of Sufi culture all around. It seeped into the conversations, the poetry, and even the songs that people sang at functions. The concept of wooden shrines and their welcoming courtyards was one where people could come with or without questions.

On Urs days across Urs villages, the big day is when people make traditional food and publicly distribute it. This is when everybody felt they belonged to something bigger than themselves. The elders would talk to the kids about the life stories and teachings of the saints. Treating guests and elders with respect, and helping out others in the neighbourhood—these were all influences brought forward by Sufi Islam. Almsgiving and mutual aid were not preached; they were lived.

Sufi shrines have always had this open-door policy. Every kind of person, of every kind of religion, would show up there—hoping not just for health, peace, and comfort, but desperate for them. And amidst all this, somehow, trust was built. Despite all the tension, people would still find themselves in these shrines, remembering what they had in common. Some way, somehow, these traditions managed to calm everyone down.

But lives shifted. These days, a lot of young people spend more time scrolling than hanging out in real-life gathering spots. Moving to cities has chipped away at old neighbourhood bonds. Some shrines don’t see the crowds they used to, and those old poetry circles or storytelling nights? They’re fading too.

Politics and unrest haven’t helped. Cultural events get interrupted, and some families just drift away from old habits. In some places, the bustle of shops and markets around shrines steals the spotlight from spiritual learning. Scholars worry about this—if no one steps up, younger generations might lose touch with traditions that used to mean so much.

Still, shrines like Dastgeer Sahib and Naqshbandi Sahib stand strong. They’re more than buildings; they hold memories—of tough times, big celebrations, stories passed down. When Urs or special prayers come around, people still gather: listening to sermons, sharing food, catching up with family.

Bringing shrine spaces back to life could spark a cultural revival. Clean them up, organize regular events, get young people involved as volunteers—suddenly, the whole community feels more connected. Bring back poetry nights or storytelling, and people start to rediscover the wisdom of the saints. Even something like a heritage walk can give kids and teens a real sense of history—shrines become classrooms, not just old walls.

The future? It’s in the hands of young people. Schools can weave local heritage into lessons—let kids learn how Sufi saints shaped Kashmiri society. Teachers can put on cultural days: let students try their hand at poetry, short plays, anything that connects them to the past. Colleges can open up bigger conversations about spirituality, ethics, what it means to serve your community.

And yeah, digital media’s a huge piece of this now. Short videos, podcasts, online galleries—these can bring Sufi teachings to a whole new audience. Youth groups can collect stories from elders, capturing memories before they fade. This kind of sharing bridges generations and keeps old stories alive.

Volunteering, powered by Sufi values, can make a real difference too. Young people can pitch in—help maintain shrines, organize charity events, run community kitchens during Urs. These experiences teach empathy and responsibility, and remind everyone that tradition isn’t just about the past—it’s about what you do, right now.

In Kashmir, Sufi music and poetry aren’t just art forms—they’re the soul of the culture. When people gather for devotional songs, you can feel the energy in the room. The musicians don’t need fancy words or complex instruments. They stick to the basics, but somehow, those simple tunes and lyrics bring everyone closer, weaving spiritual lessons right into the heart. Some of the older singers still show up during Urs celebrations. Their voices carry a lifetime of memories—listening to them is like stepping back in time.

If you want to keep this culture alive, you can’t just rely on big organizations. Sure, music festivals and poetry nights are great for spotlighting local talent, and art exhibitions with spiritual themes can pull in younger crowds. Recording traditional songs and saving them digitally helps too—otherwise, it’s too easy for those treasures to disappear. Workshops that teach classical and folk Sufi styles are another way to keep the old skills alive.

But honestly, it’s not enough to leave everything to institutions. Real change starts at home and in the neighbourhood. Families can tell stories about saints and read out old poems around the dinner table. Local groups can organize small gatherings, where elders share what things were like before. And during Urs, community kitchens don’t just feed people—they remind everyone what collective participation feels like.

Grassroots groups can set up heritage walks or storytelling evenings. Local writers and journalists can dig up stories about little-known saints and forgotten shrines, bringing them back into the spotlight. Even a well-crafted social media campaign focused on culture and history can get young people interested.

Of course, the government still has a role. Restoring shrines and protecting old manuscripts takes real investment. Cultural departments can fund music festivals and research. Tourism built around spiritual heritage brings in money, but more importantly, it encourages outsiders to respect these traditions.

Museums and cultural centres can do their part by displaying manuscripts, photos, and artifacts from Sufi history. Universities can launch research programs that document oral stories and customs. When scholars and community leaders team up, the result is a more honest and balanced approach to preserving culture.

The teachings of Kashmiri saints—humility, compassion, peaceful coexistence—are as urgent today as ever. Public discussions and interfaith dialogues can help bring back a culture of respect. Cultural exchanges between different regions open doors and break down old prejudices.

Sufi ideas aren’t just for show. They’re meant to be lived—helping neighbours, feeding people in need, solving problems by talking things out. When these values show up in daily life, cultural revival isn’t just an empty gesture.

Reviving Sufi culture in Kashmir asks for real commitment from everyone—individuals, families, communities, institutions. This heritage shaped literature, music, architecture, everyday life—anchoring everything in compassion and shared responsibility. Now it’s up to the next generation to rediscover these traditions, whether through education, art, or just pitching in at the local shrine. Writers, teachers, and artists need to keep telling the stories that tie yesterday to today.

Bringing culture back doesn’t mean trying to live in the past. It’s about holding onto the values that make harmony and mutual respect possible. When people invest in their roots, social bonds grow stronger and hope comes back into the picture. With everyone working together, Kashmir’s legacy of peace and humanity can last for generations.

Writer is a student and columnist and can be reached at mdmuslimbhat@gmail.com

Comments are closed.