The Argument of Contingency: Existence of the Universe and God

Waseem Akram

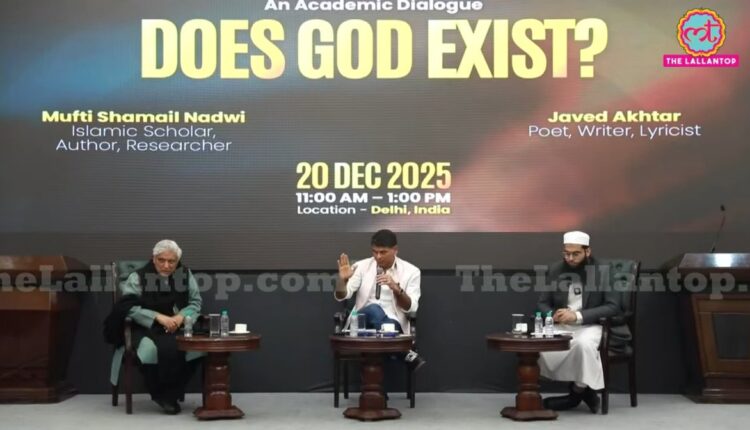

A few days ago, a public debate held at New Delhi’s Constitution Club captured widespread attention on social media. The discussion, titled “Does God Exist?”, featured noted lyricist and intellectual Javed Akhtar and Islamic research scholar Mufti Shamail Nadwi. While the exchange itself was civil and thoughtful, one philosophical term used repeatedly during the debate—contingency—became the focal point of public curiosity.

The reluctance of one participant to engage deeply with the concept sparked intense discussion online. Was the concept misunderstood, underestimated, or deliberately avoided? That question remains open. What is undeniable, however, is that the argument of contingency deserves careful explanation, for it lies at the heart of classical philosophical reasoning about the existence of God.

To understand the argument of contingency, one must first grasp two foundational metaphysical concepts: Contingent Being (Mumkin al-Wujūd) and Necessary Existent (Wājib al-Wujūd). A contingent being is something whose existence is not necessary in itself. It exists, but it could just as easily not have existed. Its presence depends on external causes.

By contrast, a Necessary Existent is that whose existence is intrinsic, self-sufficient, and independent of all other causes. Such an entity does not derive existence from anything else and cannot cease to exist. Classical Islamic philosophy asserts that only God fits this description.

Modern cosmology, particularly the Big Bang theory, indirectly supports the idea of contingency. The theory describes the universe as emerging from an extremely dense and hot initial state, followed by expansion, formation of matter, and eventual structuring into galaxies and celestial bodies. This scientific explanation demonstrates that the universe had a beginning and underwent transformation. However, while the Big Bang explains how the universe evolved, it does not explain why it exists at all. Science describes processes within existence, not the ultimate reason for existence itself.

Here, metaphysics steps in. The Holy Qur’an succinctly captures the idea of the Necessary Existent in Surah Al-Baqarah (2:255):

“There is no deity except Him, the Ever-Living, the Sustainer of all existence.”

This verse highlights God as self-subsisting, independent, and the ultimate ground of all reality.

The philosophical formulation of this idea was most rigorously articulated by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) in his famous “Proof of the Truthful” (Burhān al-Ṣiddīqīn). Ibn Sina argued that everything in the universe is contingent—it requires a cause to exist. If every cause were itself contingent, the chain of causation would regress infinitely. Such an infinite regress, he reasoned, cannot satisfactorily explain existence. Therefore, there must exist a first cause that is not contingent—an uncaused, necessary being that gives existence to all contingent things. This being, by definition, is God.

To illustrate contingency in simple terms, consider a human being. A person exists because of parents, food, air, water, and countless environmental factors. None of these are self-sufficient either; they too depend on other causes. This layered dependency reveals that existence itself is borrowed, not intrinsic. The argument of contingency insists that this chain cannot go on endlessly without grounding itself in a being that exists by necessity rather than dependence.

Imam Al-Ghazali later refined this reasoning through what is now known as the Kalam Cosmological Argument. While Ibn Sina focused on metaphysical necessity, Al-Ghazali emphasized temporal beginning. He argued that an actual infinite cannot exist in reality, and since the universe is composed of events occurring in sequence, it must have had a beginning. Anything that begins to exist requires a cause. Thus, the universe, being contingent and finite in time, must depend on a non-contingent, eternal cause. Even if every individual component of the universe were explained, the universe as a whole would still require an explanation beyond itself.

Modern physics has, in some respects, strengthened these arguments. Einstein’s theory of relativity describes space and time as interconnected and dynamic rather than eternal absolutes. This suggests that space-time itself had an origin. If time and space began, they cannot be self-existent. They are contingent realities. While science stops short of naming a metaphysical cause, it increasingly points toward a universe that is not eternal or self-sustaining.

The second law of thermodynamics further reinforces this reasoning. It states that entropy—or disorder—in a closed system tends to increase over time, eventually leading to a state of maximum entropy where no usable energy remains. If the universe were eternal, it would have already reached this state. The fact that it has not suggests a finite beginning—a point when order existed. This again supports the idea that the universe is contingent and requires an external, non-contingent source.

The Qur’an repeatedly emphasizes this dependence of creation on God, contrasting human choice and freedom with divine necessity. While human beings exercise free will, their existence and capacity to choose are not self-generated. God alone is described as eternal, independent, and self-sufficient. Contingency, therefore, is not merely a philosophical abstraction but a deeply embedded theological principle.

It is important to note that contingency is a metaphysical concept. It cannot be measured by laboratory instruments or verified through empirical experiments. Science explains mechanisms; metaphysics addresses foundations. Confusing the two leads to category errors. The question of God’s existence belongs not to experimental science but to rational philosophy and metaphysical reasoning.

One of the most striking aspects of the Constitution Club debate was its tone. An atheist intellectual, an Islamic scholar, and a Hindu mediator engaged in a serious philosophical discussion without hostility or disrespect. In an age of polarisation, such dialogue is rare and deeply valuable. Disagreement was expressed without ridicule, and conviction without contempt. This itself reflects the spirit of a democratic and plural society, where ideas are debated on their merit rather than silenced through aggression.

The argument of contingency does not compel belief, but it does compel reflection. It invites us to ask not just how the universe functions, but why it exists at all. Whether one accepts its conclusion or not, it remains one of the most enduring and intellectually rigorous arguments in the history of human thought—bridging theology, philosophy, and even modern science.

The author is an academician and columnist and can be reached at waseemche11@gmail.com

Comments are closed.