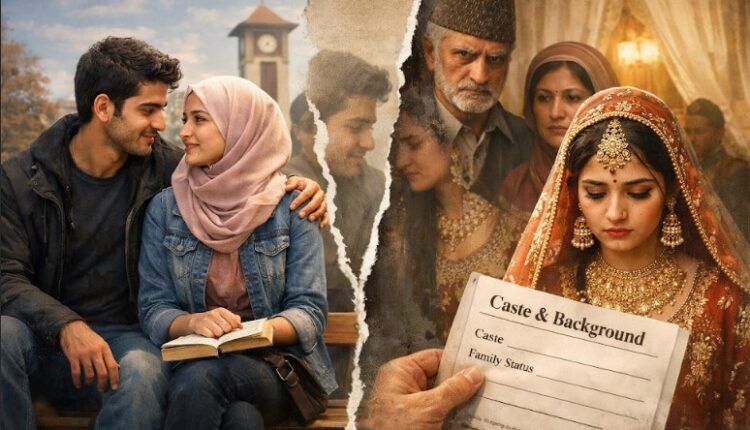

Adrenaline in Adolescence, Caste at Marriage: A Kashmiri Reality

Aadil Rashid

“Adolescence is allowed emotional space precisely because it is assumed that adulthood will restore obedience. Adrenaline is permitted; autonomy is not. Caste, meanwhile, remains non-negotiable.”

As a medical student, I am trained to view adolescence not as a moral deviation, but as a clearly defined biological and psychological phase of human development. Medical science does not treat youthful emotions as recklessness or rebellion. It understands them as a natural outcome of hormonal changes, neurological restructuring, and the gradual maturation of emotional regulation. Yet, outside lecture halls and clinics, adolescence in Kashmir is rarely interpreted through this scientific lens. Instead, it is judged through social convenience—tolerated briefly, dismissed casually, and tightly controlled the moment tradition demands conformity.

From a medical perspective, adolescence and early adulthood are periods of heightened emotional intensity. During these years, the limbic system—the part of the brain responsible for emotions, reward, and attachment—develops earlier than the prefrontal cortex, which governs judgment, impulse control, and long-term decision-making. This neurological imbalance is not a flaw; it is a universal developmental reality. It explains why young people are naturally drawn toward emotional bonding, companionship, and intimacy. These inclinations are not signs of irresponsibility. They are part of how the human brain learns connection, trust, and emotional resilience.

In Kashmir, this phase unfolds in colleges, universities, workplaces, and increasingly, digital spaces. Young men and women form relationships rooted in shared academic pressures, emotional understanding, intellectual companionship, and mutual support. In a region shaped by prolonged conflict, uncertainty, and psychological strain, such bonds often serve as emotional anchors. From a clinical standpoint, they can function as protective buffers against anxiety, loneliness, and emotional isolation.

Families often tolerate these relationships, but only conditionally. They are dismissed as “just a phase,” something youth will naturally outgrow. Emotional freedom is allowed, but only as long as it does not challenge entrenched social structures. The tolerance is temporary, not principled.

The contradiction becomes unmistakable when the subject of marriage arises. A simple declaration—ab shaadi ka waqt hai—marks a sudden shift. What was once ignored as adolescent impulse is now subjected to rigid social scrutiny. Individual choice gives way to collective authority. Emotional bonds are no longer evaluated on compatibility or mutual respect, but on lineage, surname, family background, and social standing.

It is at this point that caste, often claimed to be muted or irrelevant in Kashmir, reasserts itself with quiet force. Though rarely spoken of openly, caste continues to shape marital decisions through subtle yet decisive markers—ancestral occupation, village reputation, family history, and social networks. Emotional compatibility, which medical science recognizes as central to long-term mental health and relational stability, is pushed to the margins.

From a psychological standpoint, this abrupt transition is deeply disruptive. Individuals may not describe the experience as trauma, yet its effects surface quietly in the form of anxiety, emotional suppression, depression, and withdrawal. The mind is forced to detach from bonds it once considered legitimate, without any framework for processing the loss.

This silent cost is most visible in women. Relationships formed during formative years are invalidated, as if they never existed. Unlike bereavement, this loss carries no rituals, no acknowledgment, and no socially sanctioned space for healing. The grief is private, often internalized, and therefore invisible.

Women bear a disproportionate emotional burden. Their past attachments are scrutinized and moralized, while men are frequently encouraged to “move on” without interrogation. Women are expected to erase memory, attachment, and emotional investment in the name of social order. This expectation extracts a lasting psychological toll—one that medicine is only beginning to document in conservative societies where emotional expression is tightly regulated.

What society effectively does is grant temporary freedom to biology while preserving hierarchy as permanent. Adolescence is allowed emotional space precisely because it is assumed that adulthood will restore obedience. Adrenaline is permitted; autonomy is not. Caste, meanwhile, remains non-negotiable.

For a medical student, this raises an ethical dilemma. Biology cannot be selectively acknowledged—respected when convenient and ignored when it challenges social comfort. Emotional bonds formed during adolescence are neurologically real and psychologically enduring. They do not dissolve simply because society demands they should. Dismissing them does not strengthen social cohesion; it merely postpones emotional consequences.

As Kashmir’s youth become more educated and increasingly aware of mental health, this contradiction grows harder to justify. A society that invests in scientific education, psychological awareness, and modern healthcare cannot simultaneously uphold social practices that disregard emotional well-being. The gap between what medicine understands and what society permits is widening—and the cost is borne quietly by individuals, particularly women.

Adolescence is not a mistake that needs correction in adulthood. It is a foundation. Emotional experiences during these years shape attachment styles, self-worth, and long-term mental health. Ignoring this reality does not preserve tradition; it undermines human development.

Only when social structures begin to align with biological and psychological realities can love, choice, and mental well-being coexist without contradiction. Until then, Kashmir will continue to tolerate emotion in youth, deny it in adulthood, and silently bear the mental health consequences of that denial.

Comments are closed.