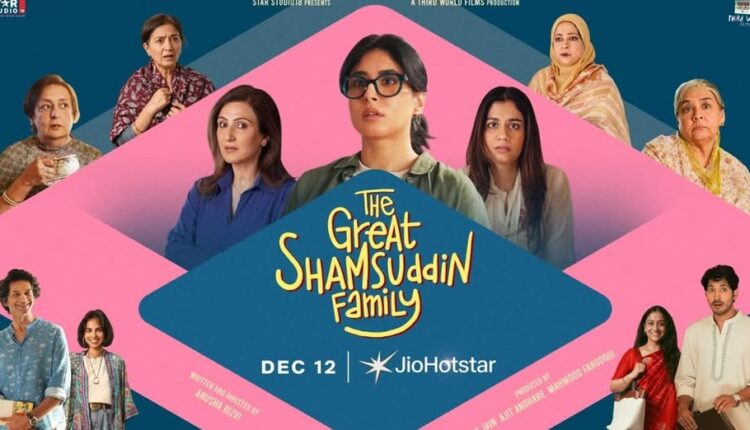

Why Ordinariness Matters? Realism and Resistance in The Great Shamusddin Family

Dr. Toyeba Mushtaq

“In contemporary Indian cinema, Muslim representation is frequently mediated through spectacle, moral polarisation, and ideological excess. The Great Shamusddin Family offers a deliberate departure from these dominant regimes. It replaces spectacle with ordinariness, insisting that everyday life itself can be a mode of political resistance.”

Comments are closed.