Chhamb 1971: Where 9 JAT Turned Desperation into Defiance

By Brig R. A. Singh, VSM (Retd.)

The story of 9 JAT in the Battle of Chhamb, 1971 remains one of courage, sacrifice, and unacknowledged heroism. It is a chapter of the 1971 India–Pakistan War that deserves to be remembered not only for the ferocity of combat but also for the resilience of soldiers who stood their ground in circumstances that tested human endurance beyond measure.

In September 1971, 9 JAT was mobilised as part of 68 Infantry Brigade and moved from Khrew in Jammu and Kashmir to the Akhnoor sector. The battalion was placed under 10 Infantry Division and earmarked for the planned Indian offensive aimed at reclaiming the Chhamb sector lost in the 1965 war.

The unit concentrated in the general area of Akhnoor for intense training and coordination. Reconnaissance was undertaken personally by all commanders up to platoon level. Dressed in BSF uniform for concealment, officers and men carried out deep recce missions—almost 30 kilometres inside Pakistani territory—covering forward posts such as Bokan and Dalla near the Chhamb sector. These were risky missions conducted under cover of secrecy to familiarise themselves with future assault routes and objectives.

At the same time, the battalion carried out rigorous infantry–tank cooperation training in the Jaurian (PDC) area alongside 9 Deccan Horse, preparing for combined operations. Morale was exceptionally high. The battalion formed part of 68 Infantry Brigade (Corps Reserve) and was eager to participate in the offensive to avenge the loss of Chhamb from the earlier war. Preparations were thorough, and the troops were mentally attuned to the role they were about to play in shaping the western front of the conflict.

However, events took an abrupt and unexpected turn. On 3 December 1971, Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on Indian air bases, marking the formal outbreak of war. The operational posture of 10 Infantry Division was immediately altered. What had been planned as an offensive campaign became an urgent defensive operation.

Indian formations had to hold ground instead of attacking. In this altered context, 9 JAT received sudden orders to move to the Pallanwala sector and take up defensive positions on the eastern bank of the River Manawar Tawi.

The movement began on 4 December 1971, entirely on foot along the Akhnoor–Pallanwala axis. This was a tense and demoralising march. Along the route, 9 JAT encountered withdrawing troops of 191 Infantry Brigade, who had been forced to abandon their permanent defences across the Manawar Tawi under heavy Pakistani pressure. These troops were falling back while Pakistani armour and infantry pursued closely behind them. For the soldiers of 9 JAT, advancing into an unfamiliar sector while witnessing a retreat ahead could have broken morale—but it did not.

Compounding the stress of the situation, Pakistani artillery observation posts infiltrated alongside the withdrawing Indian troops and soon opened accurate artillery fire onto the movement routes of 9 JAT’s columns. Despite this harassing fire and the physical strain of forced marches, the battalion maintained discipline and reached the Pallanwala area intact and with strong morale.

Upon arrival, the battalion found itself in a grave tactical predicament. There were no prepared defences. Battalion Headquarters occupied the bathing cubicles of a well near a school as makeshift shelter because the enemy shelling was intense and open areas offered no cover. Companies moved forward to establish hurried defences along the eastern bank of the Manawar Tawi, but the terrain itself presented formidable obstacles. The area was thick with 10-foot-high sarkanda grass, interspersed with boggy, marshy patches that restricted movement. For administrative reasons, platoon localities were placed about 50 metres behind the river line, leaving soldiers without clear fields of fire or effective observation over the expected enemy crossing points.

The battalion had no minefields, almost no defensive stores, no attached artillery observation post, and critically, no armour support, even though it was guarding the likely tank ingress routes near the Raipur and Darh crossing points. Defensive positions were scraped out hastily over just four to five days under shellfire.

To worsen matters, the battalion had only recently shifted organisational equipment from Mountain (“M”) to Plains (“P”) establishment, and its six RCL guns were rushed from Mumbai. There was no time to conduct proper training with the detachments before deployment. The battalion therefore entered battle under grave material and tactical handicaps.

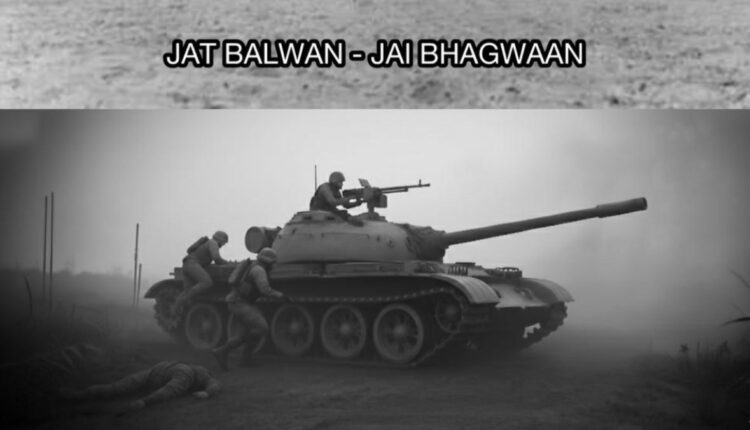

The Pakistani assault began at 0100 hours on 10 December 1971. The attack was launched by 111 Brigade of Pakistan’s 23 Infantry Division, supported by tanks from 28 Cavalry, directly opposite the Darh and Raipur crossings. In the opening phase, enemy armour overran the two forward companies of 9 JAT and then struck the depth company. There was no Indian armour to counter the tank onslaught. This became a raw and desperate infantry-versus-tank battle.

The courage displayed by the soldiers of 9 JAT during these moments was extraordinary. Some jawans climbed onto advancing enemy tanks. Others stood their ground firing SLR rifles at armoured vehicles at point-blank range, knowing full well that the odds were impossible. Many died where they stood. Yet, not a single trench was abandoned. Despite devastating losses, the men of 9 JAT refused to yield.

When the enemy infantry followed the tank assault, 9 JAT countered fiercely. The infantry waves were repulsed with heavy Pakistani casualties. However, the price paid by the battalion was immense. Three officers, three JCOs and seventy-six other ranks were killed. An almost equal number were wounded. The battalion effectively lost the strength of two complete rifle companies, including their commanders, in a single night of fighting.

Despite this enormous attrition, the surviving troops held their positions throughout the day of 10 December. Their steadfastness provided a firm base for 10 Infantry Division’s counter-operations aimed at regaining lost ground. Fate also offered small mercies. The terrain around the Manawar Tawi crossings was too boggy for the enemy tanks to manoeuvre effectively, preventing them from exploiting their breakthrough. Additionally, the General Officer Commanding Pakistan’s 23 Infantry Division was killed in a helicopter crash on 10 December, and command passed to an artillery commander who chose not to continue aggressive ground exploitation. Pakistani forces eventually withdrew west of the river, sparing Indian formations from deeper breakthroughs toward Akhnoor.

In spite of their numerical and equipment superiority, Pakistani forces failed to penetrate further. Subsequent attacks were beaten back by the exhausted yet determined soldiers of 9 JAT occupying their fragile positions. It was resolute leadership, unit cohesion, and unwavering determination that turned a desperate defensive stand into a strategic success. The battalion’s actions halted the enemy advance and prevented the fall of Akhnoor, a position whose loss could have had severe operational consequences.

Yet, tragically, this sacrifice went largely unrecognised. Because 9 JAT was part of Corps Reserve, and because the overall Chhamb campaign ended unfavourably for India—with Chhamb once again falling into Pakistani hands—the battalion’s achievements were overshadowed. Operational setbacks at formation level obscured the fact that it was the stand at Manawar Tawi that stopped the enemy’s forward thrust.

Each year on 10 December, 9 JAT pays homage to its fallen heroes. The purpose of recalling this history today is not merely to honour memory but to seek rightful recognition. In real terms, it was 9 JAT that halted Pakistan’s advance toward Akhnoor, doing so at extraordinary cost and in conditions of extreme deprivation.

The soldiers of 9 JAT fought not for individual awards or commendations, but for the honour of their unit, the pride of the Jat Regiment, the dignity of the Qaum, and the safety of the nation. Their courage stands as a testament to the highest traditions of the Indian Army. The story of Chhamb may record defeat of territory, but it must also record victory of spirit — a spirit embodied by the men of 9 JAT on 10 December 1971.

Their valour deserves remembrance, recognition, and an enduring place in India’s military history.

Author is Former Adjutant, 9 JAT during the Battle of Chhamb, 1971

Comments are closed.